A self-funded researcher’s work shows how a flooded river basin cut ties between African communities for 40,000 years

Hannah Brightley

If archaeology brings to mind images of Indiana Jones macheting his way through the jungle, or someone sifting through dirt for an ancient tool, two scientists have recently challenged this narrative with their Nature publication, with no whip, machete or field work.

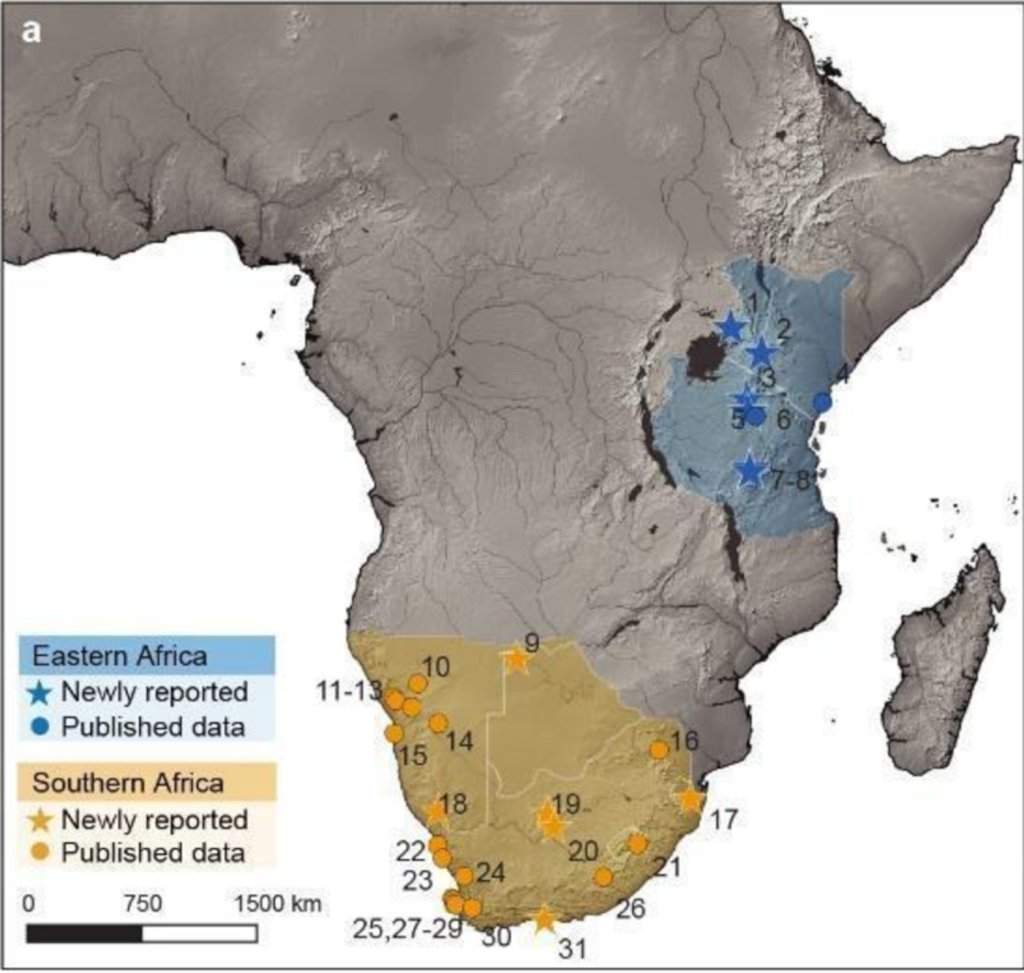

Jennifer Miller and Yiming Wang of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, instead studied ostrich beads stashed away in collections to reconstruct the interactions of eastern and southern African populations over the last 50,000 years. That diligent study was all it took to identify the oldest regional connection between the two populations.

A practice steeped in culture and history

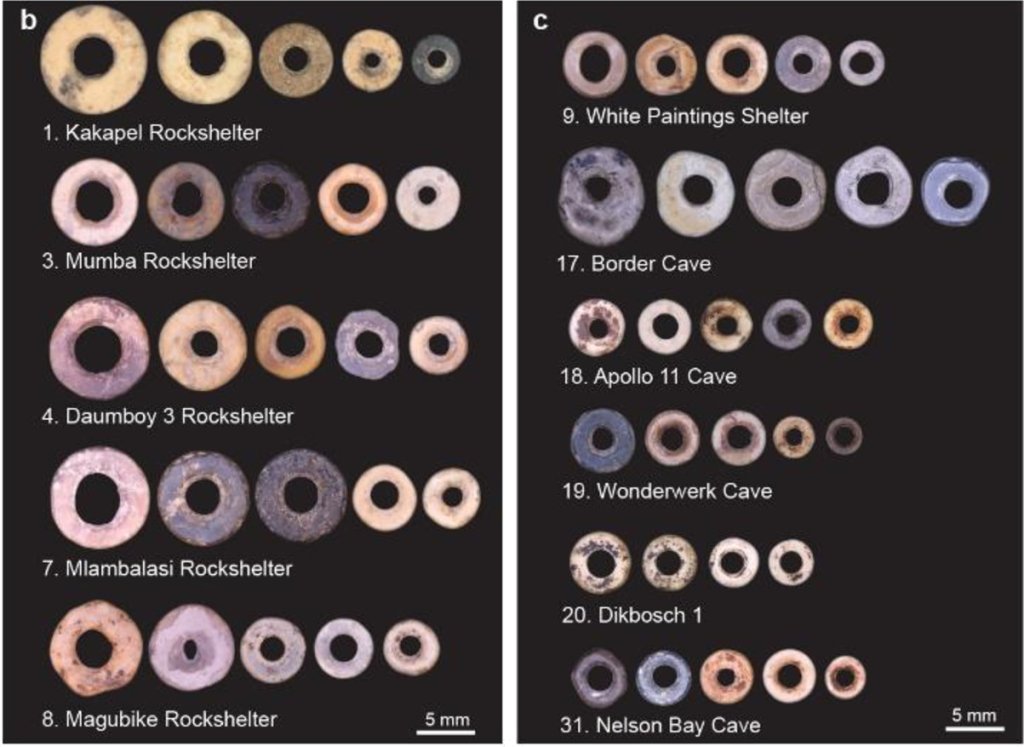

Ostrich egg beads emerged in eastern Africa 52,000 years ago, but found their way into southern African archaeological records only 10,000 years later. The practice of bead-making enriched and expanded populations’ social networks. Even today, these beads are used to communicate which group someone belongs to, their identity, or social status.

Making ostrich beads is time-intensive. So scientists believe that their presence in the archaeological record is a sign that the population was healthy enough to dedicate time to the craft. Each bead, or set, can be unique, so similarities that arise (at a time people did not communicate across the world) may be because these populations were interacting.

An investment in archaeology

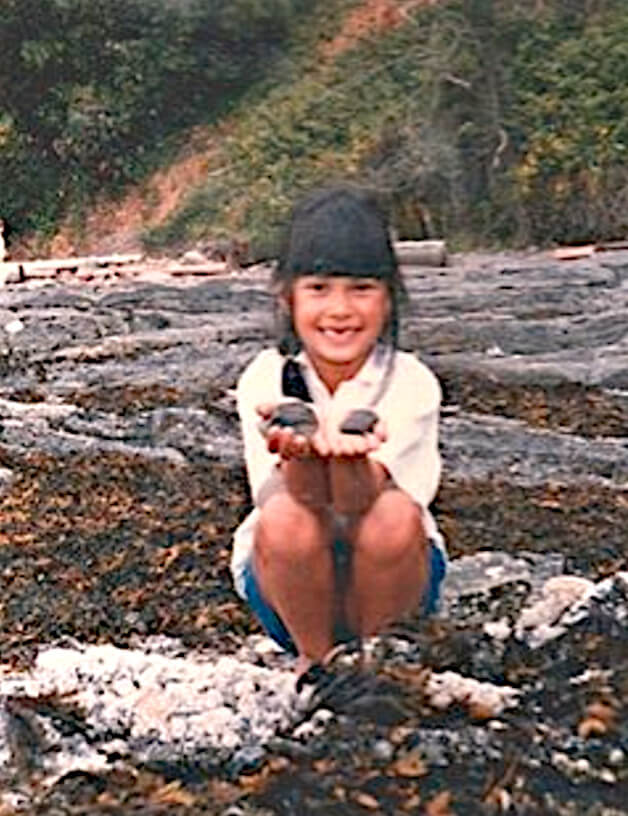

Ever since reading about human evolution in the book ‘”Time Traveller” as a 6 year old, Miller gained a passion for archaeology. But the idea for this paper only came to her when, as a master’s student, she noticed that the bulk of ostrich bead research was focused on southern African finds. Yet, there was evidence they were found elsewhere on the continent, too.

When she began work on her PhD, Miller tried to get funding to study the collections at various museums, but granting agencies tend to prefer archaeology with shovel, trowel, pick and brush to what she was proposing: a diligent study of material already collected and gathering dust in museum repositories.

So Miller marshalled her resources and her courage, and self-funded a four-month trip to South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia.

As she told the University of Alberta’s Folio, “I sat in the airport waiting to go on a trip I was paying for myself — one nobody else believed in. I was crying and thinking, ‘What am I doing? I can’t believe I’m doing this. Is this stupid?’”

It might have been. Fortunately, her mother, Karen, was with her, either because she was fearful about her daughter travelling alone, or because she was hoping to have a relaxing vacation.

Miller hired her mother as an unofficial research assistant, working 10-11 hour days, which naturally killed any hopes of that vacation. As she told Folio, “It was three months measuring beads in the backroom of museums for as long as they would let us stay. But I was then terrified to process the data. For about a year I didn’t touch it because I was worried it would show nothing, or some sort of totally random pattern.”

On and off, it took Miller 10 years to collate the full data set. When she finally studied the material, she found she was onto something.

“I’m really glad that it paid off; whenever I have doubts about things now, I think back to that time,” she told Folio.

Even after completing her PhD, the significance of her work went largely unnoticed.

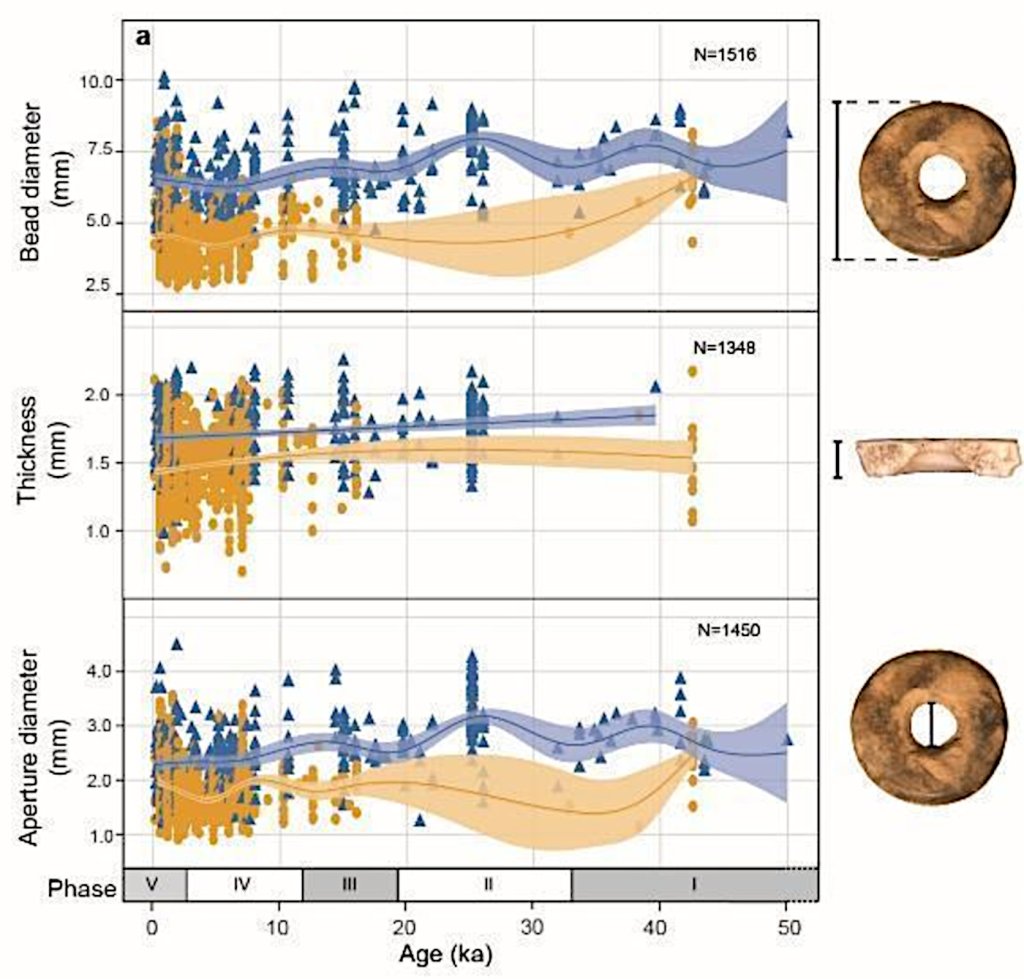

Her PhD dataset (which forms the basis of this paper) includes measurements of 1,516 individual beads from 31 archaeological sites, 1,238 of which have never been fully reported before.

Then she got a postdoctoral position at the Max Planck Institute. And that led to a serendipitous series of events leading to the publication of the paper.

Collaborations

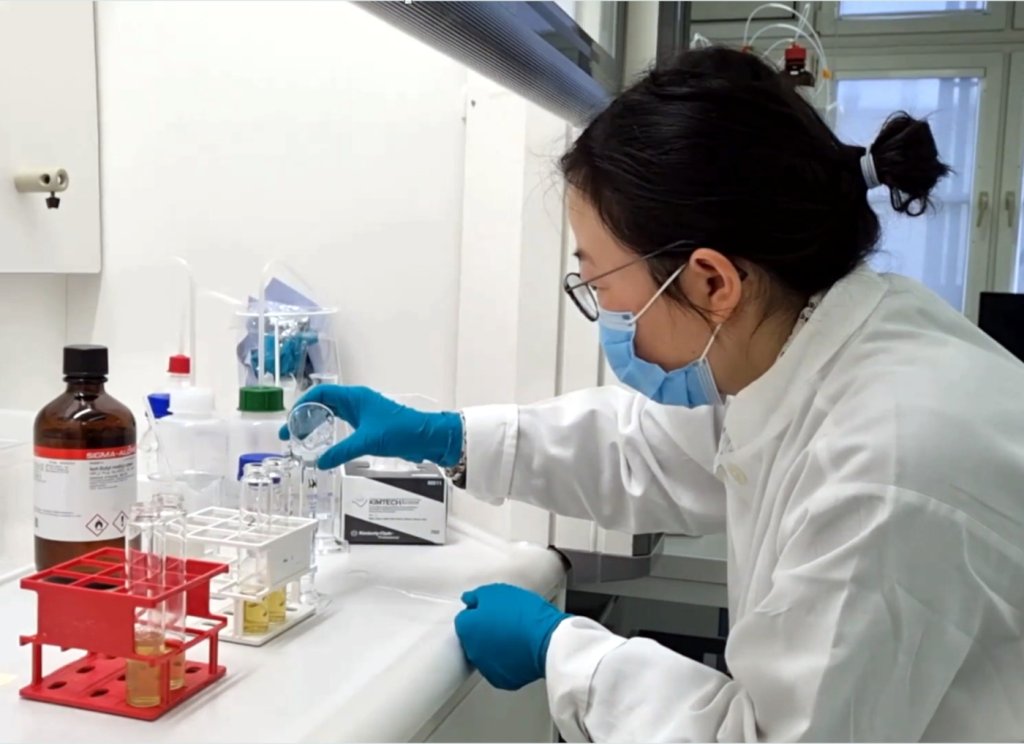

Wang, an expert in paleoclimate and data analysis, was at the Max Planck Institute for the onerous task of researching biomarkers from ancient “poop” (her words). Part of this role involved supporting the building of the institute’s new “poop lab.” So Wang had no time to look further into Miller’s PhD dataset on ostrich beads following her presentation to the department. However, when the pandemic put the building of the lab on hold, Wang suddenly had time on her hands.

It was shortly after, when Wang and Miller both attended a scientific writing course for Nature, the idea of working together arose.

Miller and Wang found that the ostrich beads significantly differed through time between the eastern and southern collections. Whilst the eastern African bead shape remained relatively constant over 50,000 years, the southern kind varied widely over time. What was most remarkable was that the beads seemed to be nonexistent in the southern African record between 33,000 and 19,000 years ago.

When comparing the datasets, the ostrich beads from both populations were very similar right up until the time when the southern beads dropped out of the record. This suggested these populations were likely interacting and sharing the knowledge of bead craft between them. But what could have caused the sudden cut-off of this regional connection?

A key moment of success in the researchers’ journey was when Wang plotted this data against climate records from the same period.

She concluded that the reason probably lay far away.

A cool story

Around 33,000 years ago, the northern hemispheric ice sheet dumped a huge number of icebergs into the North Atlantic, in one in a series of phenomena called the Heinrich Events. The huge changes in seawater saltiness this caused pushed southward the meeting place of the trade winds in the northern and southern hemispheres. That resulted in huge rains falling on the areas between eastern and southern Africa, flooding the Zambesi river basin and cutting off contact between the groups until herders could wind their way south – about 2,000 years ago.

They both remember Wang realizing this and enthusiastically running into Miller’s office with her first plot in hand. That plot is still pinned to Miller’s office wall today.

Whilst bead-making continued in eastern Africa, Miller and Wang suggest that southern African populations might have shifted social strategies in response to the changing climate, resulting in smaller populations. These smaller groups perhaps had less need to convey social information through intensive bead-making.

All that detective work made little impression on other academics. Miller says that trawling through museum collections was “not sexy science,” and that archaeology has traditionally favored studies on adrenaline-charged activities like hunting, not “softer” skills like studying ostrich beads.

That did not stop them from getting their publication into Nature, which led to celebrations when crossing each stage in the submission process, one of which involved Miller gifting Wang a geologic time scale printed tea infuser.

As with most research, passionate and tenacious people negotiated hurdles, periods of frustration, and, with some luck, found someone with a complementary skill set. By going back over old material, and not reinventing the wheel, Miller and Wang relied on a sustainable form of archaeology to complement other approaches to understand the past.

Hannah Brightley is a science communicator based in New Zealand. She has an MSc in geology and is passionate about working with scientists to showcase their research to the general public.

Click here for the original report